Why do people eat chili cheese dogs?

That may be a strange way to begin a blog post about intimate partner violence. But bear with me. Whether you like or dislike chili cheese dogs, people have eaten them for decades and probably will continue to. So, why do we do that?

Maybe it depends on the occasion: perhaps chili cheese dogs are a staple food during football tailgating. Maybe we eat them because it’s what Dad or Mom makes (or made) for us. Maybe they’re cheap and readily available at the corner store. Maybe we just like the way they taste. Or we know they’re unhealthy for us, but maybe we eat one every once in a while as a treat.

It’s a simple question with lots of possible answers, and these answers have to do with a person’s individual tastes, but also with their surroundings, their upbringing, their traditions. Most of us don’t think about the “why” behind our everyday decisions like this one.

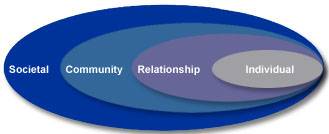

Now, intimate partner and sexual violence could not be a farther topic from eating chili cheese dogs – but the one thing they share in common is that we can examine both through the Social-Ecological Model:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention champions this framework, highlighting that it “considers the complex interplay between individual, relationship, community, and societal factors. It allows us to understand the range of factors that put people at risk for violence or protect them from experiencing or perpetrating violence. The overlapping rings in the model illustrate how factors at one level influence factors at another level.” (source)

So often, we respond to survivors of intimate partner and sexual violence by saying,

Why didn’t you leave?

I wouldn’t put up with that in a relationship.

Why didn’t you just go to the police?

These questions, while perhaps well-intentioned, miss the immense complexities of intimate partner and sexual violence, and how these complexities limit survivors’ choices. Leaving a violent relationship or seeking police or legal help are often not realistic, safe, or viable choices to survivors whose partners are isolating, controlling or threatening them.

More importantly, these questions also fail to hold the person perpetrating the violence accountable for their actions. A better question to examine is: why do people use violence in relationships?

Examined across the social ecology, some example reasons for this could include:

- Societal: the offending partner believes jealousy, controlling behavior, and violence is normal in a relationship because of stereotypes and societal expectations about being a man

- Societal again: the offending partner has been prosecuted for domestic violence before and was convicted and sentenced to 90 days in jail – so he knows that there may be legal consequences for domestic violence, but the consequences are relatively low

- Community: the offending partner’s supervisor and co-workers notices that he is constantly using work time to call and harass his partner, but they have no policy to address partner violence in the workplace, so they don’t say or do anything

- Relationship: the offending partner’s friends hear him insulting his partner and either don’t recognize it as an issue, or don’t speak up to check him on his abusive behaviors

- Individual: the offending partner feels powerful, in control, and gets what he wants when he is violent

The Social-Ecological framework puts both the survivor’s and the offending partner’s choices into context. This framework also helps us think more deeply about how to prevent violence: as the CDC states, it “suggests that in order to prevent violence, it is necessary to act across multiple levels of the model at the same time. This approach is more likely to sustain prevention efforts over time than any single intervention.

The complex problem of intimate partner and sexual violence deserves a complex and comprehensive solution. At The Center for Women and Families, we advocate for survivors of intimate partner and sexual violence, and we believe that prevention of violence is an advocacy strategy.

When we support high schoolers in developing skills to intervene in incidences of bullying or violence; when we train medical students to screen their patients for relationship violence; when we engage men in conversations about preventing sexual assault – we’re creating a community of advocates who can help survivors reclaim their power, stop violent incidents before they start, and work to uproot violent norms altogether. All by asking a different question.

Written by Caitlin Willenbrink, Training Coordinator at The Center for Women and Families